QA With Process and Playbooks, Not Pressure

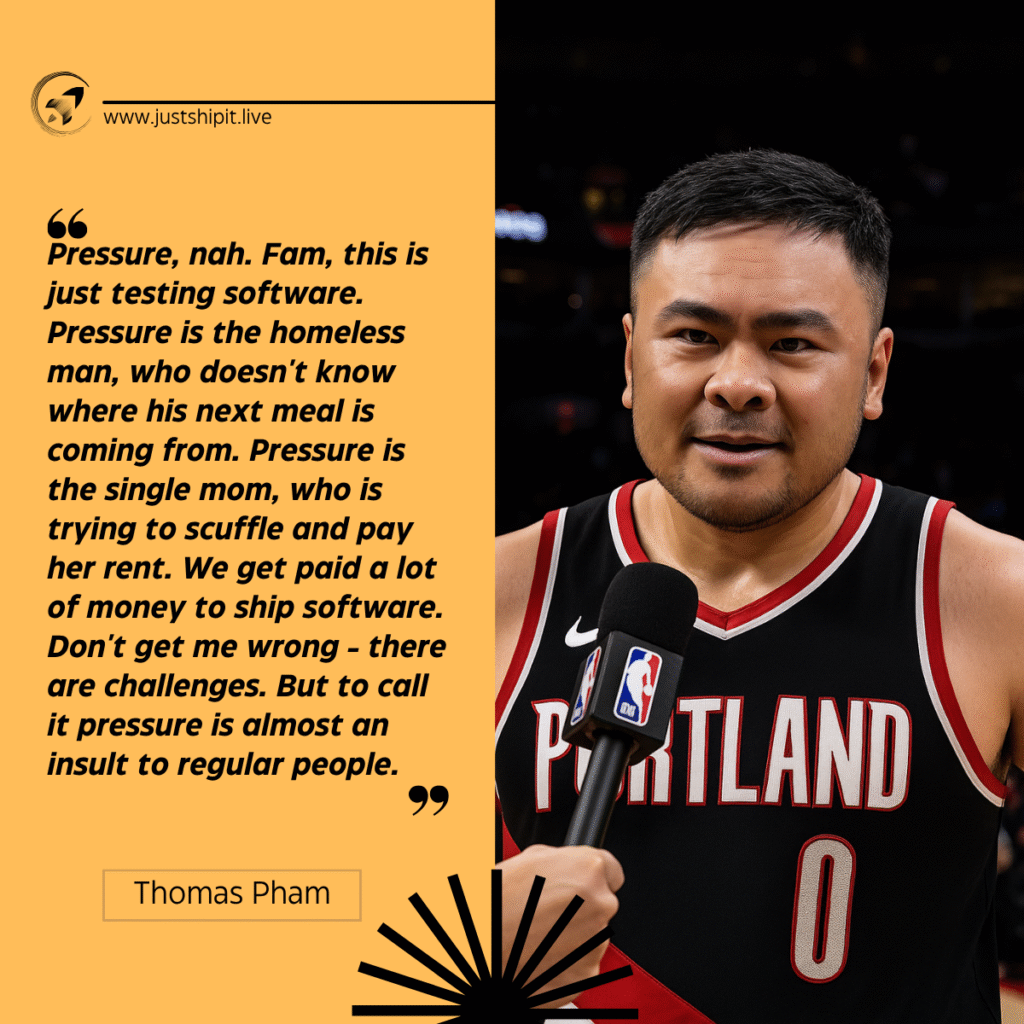

During my transitional phase, I was asked a common interview question: “Tell me about a time you worked under high pressure.” I struggled to answer this question on the spot, not because I couldn’t come up with an acceptable STAR interview answer but because I couldn’t come up with a real example. Reflection is a big part of the interview process, and after having some time to reflect, I realized the best answer might be this legendary quote from Damian Lillard:

“Pressure, nah. Fam, this is just playing ball. Pressure is the homeless man, who doesn’t know where his next meal is coming from. Pressure is the single mom, who is trying to scuffle and pay her rent. We get paid a lot of money to play a game. Don’t get me wrong: there are challenges. But to call it pressure is almost an insult to regular people.”

This perspective is a powerful reminder to keep things in context. Sure, QA can be life-or-death in some industries—medical devices, aerospace, critical infrastructure. And sometimes poor testing can literally CrowdStrike half the world offline. But for most software teams, most of the time, we’re dealing with challenges, not true emergencies.

Example #1: Finding a Bug Late in the Release Cycle

Let’s walk through a common scenario: you discover a critical bug just days before your scheduled release. This feels like a high-pressure situation, but in most mature organizations, there are playbooks for these moments—we aren’t shipping software for the first time.

What do you do?

First, assess the impact: Which customers are affected? Understanding the scope is crucial. Next, ask: Can we get a hotfix ready for them, or at least provide a workaround? If a hotfix isn’t feasible, can we document it as a known issue and communicate it transparently?

The key is to compare the cost of delaying the release versus the cost of putting the fix on the “next bus.” There’s always a next bus. This is about presenting data to decision-makers, not panicking under pressure.

Example #2: When a Critical Bug Escapes to Production

Now consider a different scenario: a critical bug has already escaped to production and is affecting live customers. This is distinct from finding a bug before release—now you’re in damage control mode.

What are your options?

Can you do a firmware downgrade or a rollback? Is an emergency hotfix feasible? What about documenting it as a known issue while you work on a permanent fix? Ideally, your release process has a playbook with multiple options for handling bug escapes.

The focus should be on rapid assessment and clear communication. Which customers are impacted? What’s the severity? What are the available remediation paths? Once again, QA isn’t about shipping perfect software; it’s about presenting data to the decision-maker so they can make informed choices.

After the Fix: Root Cause Analysis, Not Finger-Pointing

Whether you’re dealing with a pre-release bug discovery or a post-release escape, the follow-up is crucial. Once a solution is implemented, the team should focus on root cause analysis—not finger-pointing. We want to figure out, as a team, what caused the issue and how we can prevent or catch similar bugs in the future. This collaborative approach builds trust and continuous improvement.

Testing and Shipping Software Doesn’t Have to Be Stressful

Instead of trying to find candidates who are just “good at working under high pressure,” companies should focus on finding people who can defuse high-pressure situations. The goal is to create a culture where challenges are met with calm, data-driven decision-making, and teamwork.

This aligns perfectly with the philosophy outlined in It Doesn’t Have to Be Crazy at Work by Jason Fried and David Heinemeier Hansson. As they write:

Calm is protecting people’s time and attention. Calm is about 40 hours of work a week. Calm is reasonable expectations. Calm is ample time off. Calm is smaller. Calm is a visible horizon. Calm is meetings as a last resort. Calm is asynchronous first, real-time second. Calm is more independence, less interdependence. Calm is sustainable practices for the long term. Calm is profitability.

When we apply this “calm” approach to QA and software testing, we create environments where bugs are handled systematically rather than frantically. Teams with proper playbooks, clear communication channels, and reasonable expectations don’t need to manufacture pressure—they can focus on solving problems methodically and sustainably.

Final Thoughts

Remember: the real pressure is out there in the world, not necessarily in our code. By focusing on transparency, playbooks, and continuous improvement, we can turn high-stakes moments into opportunities for growth—not stress.